What is your mission within Paris 8?

I am a design engineer, in charge of orientation and professional integration at SCIO-IP of the university (joint university service for information, guidance and professional integration). Concretely, I support students in their applications to help them carry out their study projects and make their professional projects a reality. I also make university teachers aware of these issues by co-creating and co-leading long-term training modules (one semester, 18 to 34 hours). The objective of these modules is not only to “give students the codes of the professional world”; it is above all to give them confidence in their abilities by putting them into action, by confronting them with collective projects that take them out of their comfort zone but ultimately create pride. The valorization of these projects is a lever to then help them apply and negotiate their services with public or private organizations.

What was your initial need when you contacted Didask?

The actions carried out by the SCUIO-IP have a limited impact due to the disproportion between our human resources and the number of university students. However, some difficulties that we have observed, often linked to certain” Soft Skills ” (relational, emotional, methodological) are shared by all of our courses, whether artistic, economic, computer, literary, etc.

So our aim was to create online modules that any student could grasp. We did not want another “MOOC”; we wanted to maintain the fundamental principles of our face-to-face workshops: put students in action, or in a situation, encourage them to make mistakes and support them to overcome them. Above all, students should not be afraid of making mistakes, so that the advice we wanted to give them was really part of their practices.

It is a real challenge to achieve this objective without face-to-face support. Through its methodology and its scientific roots, Didask seemed capable of meeting this challenge.

What topics should you train on?

We identified a main difficulty for most university students: The ability to work collaboratively. This is the theme we wanted to focus on, while offering more technical training in parallel in search of an internship/job that remains an important concern for students. The objective was also to train us in the Didask methodology to change our practices.

Who are the recipients of this device?

They are triple. The main recipients remain University students, especially those who have group work to do. But we also hope to use these courses to Raise awareness among teachers to these themes/issues, help them identify precisely what may be bothering students and provide them with elements to transmit during their courses. Finally, the SCUIO-IP advisors are in a sense the third recipient of the device since the Didask platform and the close monitoring of their educational engineers give us keys to learning and interaction that inspire us to new experiments during our face-to-face workshops.

What are the specific constraints of Paris 8 to deploy e-learning?

Paris 8 is a university, and like most universities it offers students a digital work environment (ENT) as well as an online learning platform (Moodle). The main difficulty is therefore not technical, since it is very easy to import Didask modules into Moodle and thus make them easily accessible to students. Rather, the challenge is to make these modules visible and attractive to students., insofar as they are optional and are therefore not associated with any course: we remain a support and support service.

When we deploy the modules, it will therefore be a question of communicating in a manner that is both massive and targeted (to the students who need it the most, especially those taking distance courses); but above all, we will have to be able to convince teachers to rely on this e-learning as part of their face-to-face courses. Without this relay, the effectiveness of our modules may be limited by the lack of regularity and stimulation in learning.

The main constraint that we are going to encounter is therefore manage to articulate our e-learning in a clear and relevant way with the student learning and resource ecosystem.

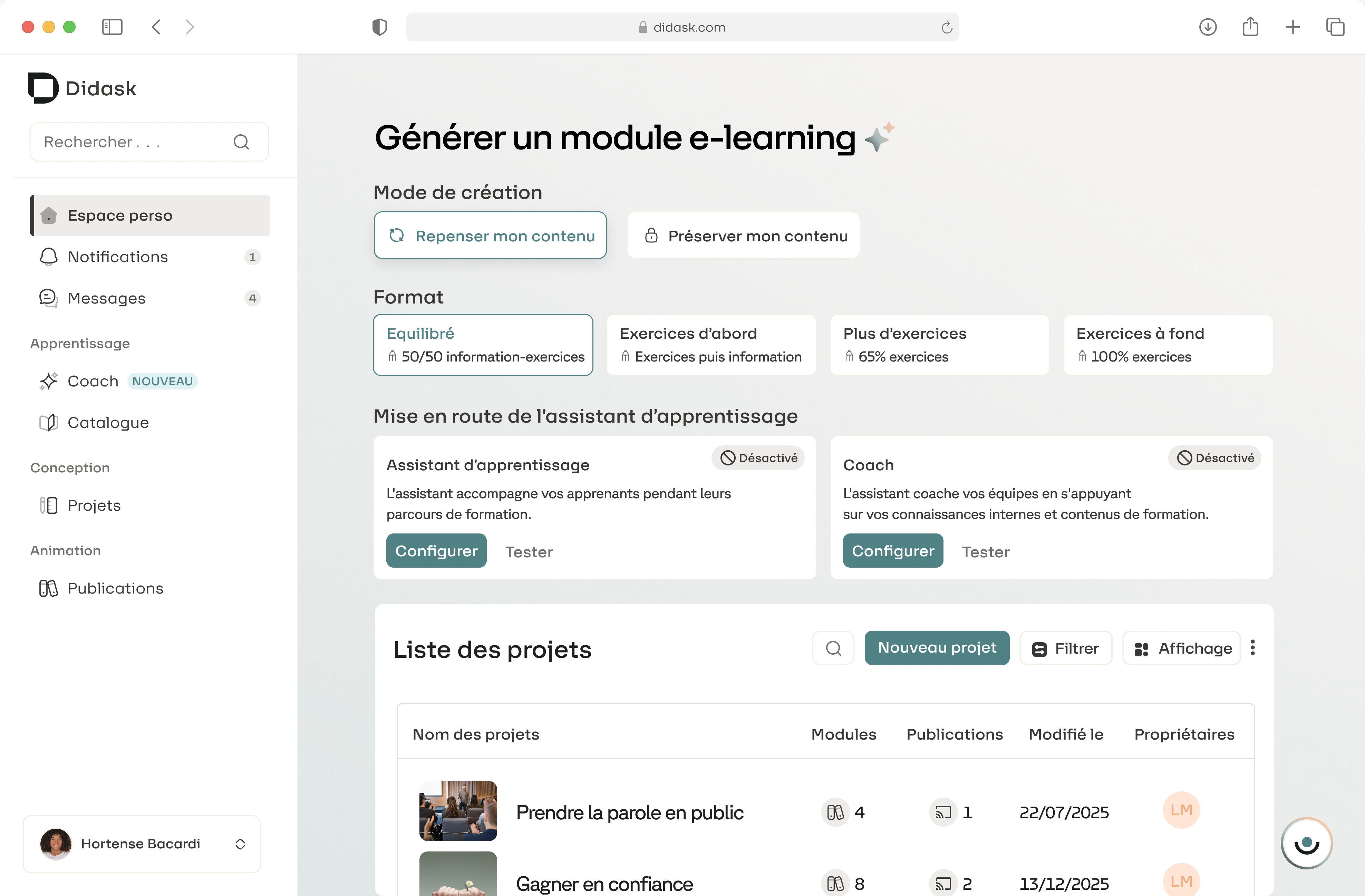

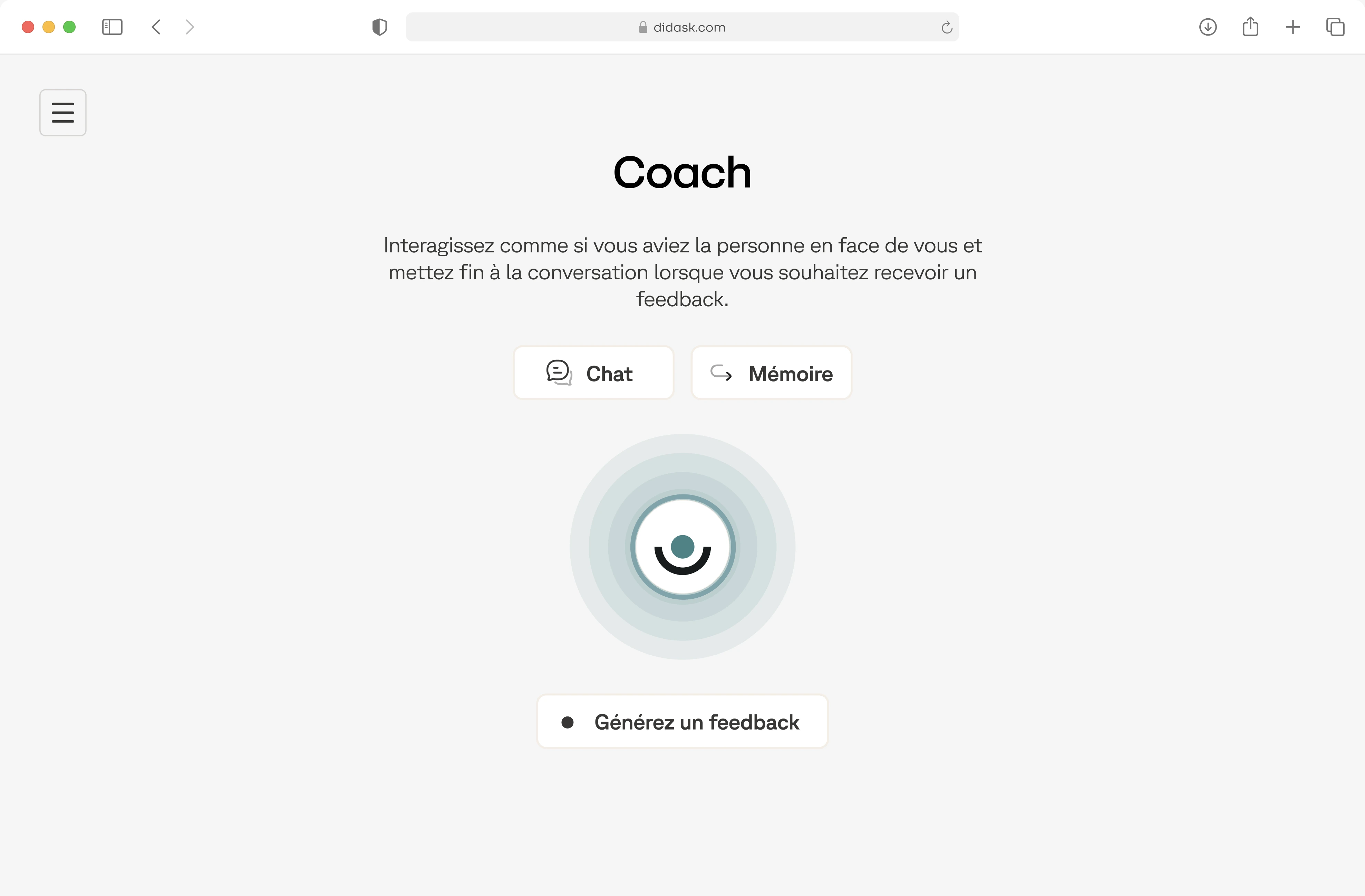

What system has been put in place with the Didask solution?

We want to launch the “Garden of Possibilities”, an ecosystem of training modules designed to help students identify their skills and develop their potential. This ecosystem, partly financed by the Ile de France Region, also includes a portfolio of skills promoting self-reflection (the PEC) and a soft skills assessment based on predictive algorithms (in connection with the company AssessFirst).

Our objective is therefore, in the long term, to provide students with a space that helps them to become aware of and value their strengths, but also supports them in the development of their potential. That's where Didask modules come in, knowing that the main axis of development of university students remains the ability to work collaboratively.

What particularities of the Didask solution make the difference for you?

Didask is based on two essential principles: the scenarios and the taking into account of” relevant errors ”. This requires us, when designing a module, to be creative and take into account the views of the students, rather than focusing only on the message to be delivered. It is a pedagogical logic that is not always self-evident, and yet it is essential to disseminate advice that is truly effective and rooted in student practices.

The fact that Didask is based on scientific work and almost like action research helps us convince university professors to take an interest in it.

What assessment do you draw from this?

Our experimentation is far from over since we are still in the training design phase. However lThe balance is already very positive for us, educational engineers, who feel that we have made progress in the way we design our actions with students.

Identify student “relevant mistakes”, reduce the” cognitive overload ” questions, summarizing our key messages... so many habits developed through the use of the Didask platform and that we have integrated into our practices!

An anecdote?

We were victims of the infiltrated agent syndrome.

When we took the platform in hand, we had difficulty creating effective scenarios: it was too easy to identify the “right answer”, which biased the entire learning process. In fact, we were so focused on sharing best practices that we didn't think hard enough about where the “mistakes” students made, which prevented us from formulating them in a relevant way. On the advice of a Didask educational engineer, we then took the time to take off our trainer hats to become students again: very quickly, we naturally committed the same “mistakes” that we regularly observed in workshops. These errors were gone, they became relevant once placed in a certain context, in connection with certain representations, apprehensions, practices.

The problem is that by reformulating and justifying these mistakes, by putting ourselves in the shoes of the students, we ended up doubting the relevance of our advice ourselves! Some questions related to group work have thus become difficult to resolve...

But this temporary schizophrenia has had an impact: our greatest satisfaction is thus to have succeeded in tricking a Didask educational engineer on a question that was apparently easy, in terms of the simulation, but that the formulation of the answers made complex. When an experienced engineer makes the same mistake as a student, it's proof that the concept of “relevant error” has been taken seriously!

.png)